Become a Pandas Wizard Overnight

You’ve Been Doing Pandas Wrong All This Time Jul 06, 25

If you are a data analyst, chances are that there would be portions of your work that you would do in pandas. And once you’ve been in it for a while, it sort of becomes second nature writing in pandas, as it’s pretty easy to build the muscle memory once you have been exposed enough to it.

Pandas is very easy to use; almost all of the functionalities there can be written with one-liners. And with that easiness, it’s also easy to write in such an unconventional manner.

There would come a time where your messy pandas code would haunt you, as it definitely happened to me. It specifically goes like this: I was creating an EDA to better understand our customers who are using buy now pay later (BNPL). As the EDA is more like an iterative process, each time I stepped away from it for a while and came back, it felt like there was a lot of friction in understanding my previous work. There also came a time when I handed it to our data scientist, and it definitely made it hard for her to read my code.

Additionally, I think this is the worst situation you would encounter: if suddenly you are in a meeting presenting your progress and then a question is asked, perhaps questioning your methodologies or asking for the specific value(s) that you got in your analysis, the answer is definitely in the code, but your code is so messy that it would take you a while to locate the answer.

Going back, this is more of a rant rather than a tutorial; I have nothing to teach but something to preach. 🫳🎤

If you want to become a pandas wizard overnight, I’ll give you this tip:

Use Method Chains

No more, no less. If there is only one piece of advice that I can give to beginners in pandas, it would be this. For example:

monthly_customer_behavior_df = paid_df.groupby(by=['customer_id', 'year_month'], as_index=False).agg(

# Transactions

no_txns=('pay_later_id', 'nunique'),

ontime_txn=('payment_status', lambda x: (x == 'ontime').sum()),

late_txn=('payment_status', lambda x: (x == 'late').sum()),

# Payment Behavior

sum_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'sum'),

avg_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'mean'),

mdn_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'median'),

days_early_list=('days_before_paid', lambda x: x.tolist()),

std_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'std'),

# Credit

avg_credit_limit=('credit_limit', 'mean'),

avg_utilization=('credit_utilization', 'mean'),

)

monthly_customer_behavior_df["payment_behavior"] = monthly_customer_behavior_df["std_days_early"].apply(lambda x: "STABLE" if x < 2.5 else "VOLATILE")

monthly_customer_behavior_df.sort_values(['customer_id', 'year_month'], inplace=True)

monthly_customer_behavior_df

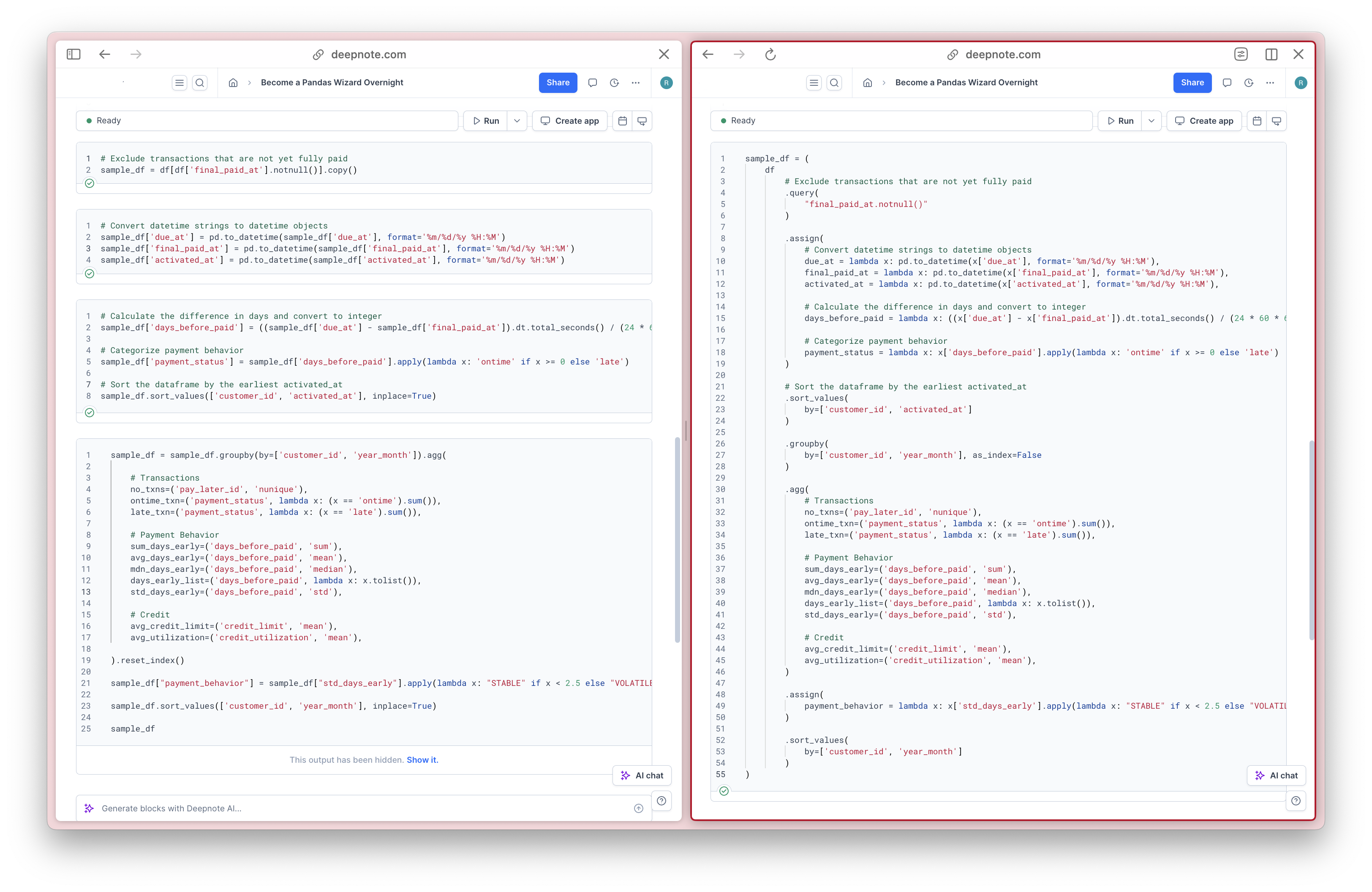

This is how people often write in pandas. You can imagine that these may be scattered across different cells in a Jupyter notebook or similar environments. To be honest, this is what most people consider clean pandas. They scan the entire notebook and delete isolated code snippets used mainly for testing and verifying data transformations. In the end, all that remains is a notebook containing various analyses. An improved version of the example above would be like this:

monthly_customer_behavior_df = (

paid_df

.groupby(by=['customer_id', 'year_month'], as_index=False)

.agg(

# Transactions

no_txns=('pay_later_id', 'nunique'),

ontime_txn=('payment_status', lambda x: (x == 'ontime').sum()),

late_txn=('payment_status', lambda x: (x == 'late').sum()),

# Payment Behavior

sum_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'sum'),

avg_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'mean'),

mdn_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'median'),

std_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'std'),

# Credit

avg_credit_limit=('credit_limit', 'mean'),

avg_utilization=('credit_utilization', 'mean'),

)

.assign(payment_behavior = lambda x: x['std_days_early'].apply(lambda x: "STABLE" if x < 2.5 else "VOLATILE"))

.sort_values(by=['customer_id', 'year_month'])

)

monthly_customer_behavior_df

Notice that all of the transformations are all contained in a single declaration where the chunk of code represents various transformations that produces a single output. Here is the visual representation of what I am trying to convey:

While the difference might seem negligible in this example, its benefit becomes apparent when dealing with a large number of data transformations.

The formatting of method chains is a matter of personal preference. Personally, I indent the method and create an additional indent for the parameters and their arguments:

monthly_customer_behavior_df = (

paid_df

.groupby(

by=['customer_id', 'year_month'], as_index=False

)

.agg(

# Transactions

no_txns=('pay_later_id', 'nunique'),

ontime_txn=('payment_status', lambda x: (x == 'ontime').sum()),

late_txn=('payment_status', lambda x: (x == 'late').sum()),

# Payment Behavior

sum_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'sum'),

avg_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'mean'),

mdn_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'median'),

std_days_early=('days_before_paid', 'std'),

# Credit

avg_credit_limit=('credit_limit', 'mean'),

avg_utilization=('credit_utilization', 'mean'),

)

.assign(

payment_behavior = lambda x: x['std_days_early'].apply(

lambda x: "STABLE" if x < 2.5 else "VOLATILE"

)

)

.sort_values(

by=['customer_id', 'year_month']

)

)

monthly_customer_behavior_df

Now, the code is so well-organized that it is effectively self-documenting. While this might be confusing just by illustrating a simple snippet, here is a real-world example of what I am trying to convey, where the common practice is on the left, and the better practice, where method chaining is utilized, is on the right.

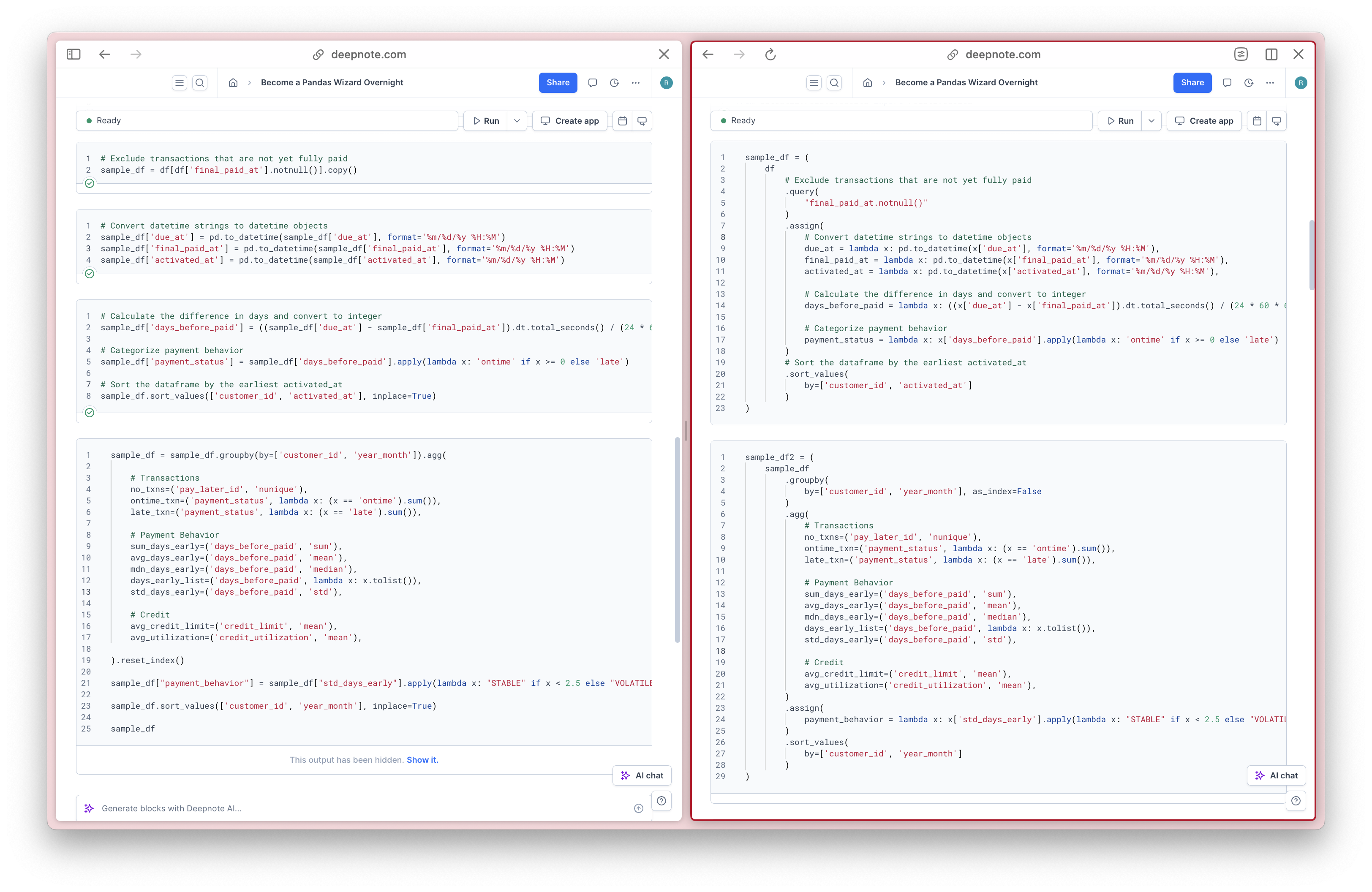

Separating these data transformations is a matter of personal preference too. If you find that the method chain becomes too long, feel free to break it up, like this one:

Once you learn this and start applying it, you would gravitate on it, perhaps you could ask adjacent questions like:

- Can I method chain on custom functions? Yes, use

pandas.DataFrame.pipe. - Can I method chain on column creations? Yes, use

pandas.DataFrame.assign. - Can I method chain on filtering? Yes, use

pandas.DataFrame.query.

Everything in Pandas Can Be Chained

If you are using pandas on a daily you may already know this, but this writing is best absorbed for practitioners who only use pandas occasionally. I didn’t read Matt Harrison’s books, but this summarizes his main idea, as stated himself at the end of this video. If you want some related tips to complement this article, you can look here; these are the best that I found prior to this writing:

PS: I could still remember the day when I first refactored my notebook to use method chains, February 21, 2025.